There is a lot of debate about the so-called tipping point for the Earth’s climate, where scientists say warming the atmosphere two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels may cause irreversible changes that could lead to global disasters.

While the number itself may or may not be realistic, the tipping point is still approaching and we need to be aware of it. There is a corollary to Murphy’s Law that states, “If you push something hard enough, it will fall over.” The interesting part of this rule is that you can push something pretty hard for a long time before it falls, and not much happens.

The simplest example of a tipping point is a glass of wine on a tray. You can tilt the tray quite far to the side and the glass will remain stable. But the angle at which the glass suddenly falls and the wine spills is very precise, and once you’re past that point, it is almost impossible to stop the fall or put the wine back into the shattered glass afterwards.

We have been pushing the climate for more than a hundred years and and haven’t seen dramatic changes… yet. But scientists are warning that a tipping point is drawing near, and doing something about it now is much easier than trying to adapt after the fall.

Stability in nature

In nature, systems can go from one stable state to another in a fairly short time.

Watch a frozen lake break up in springtime. The ice cover remains for quite a while, even after the weather warms up. Then, seemingly overnight, the lake becomes completely open water.

On either side of that tipping point, there isn’t much change — even if forces are acting on the system. Warm winter days don’t cause a frozen lake to suddenly melt, and cold summer nights don’t make it freeze.

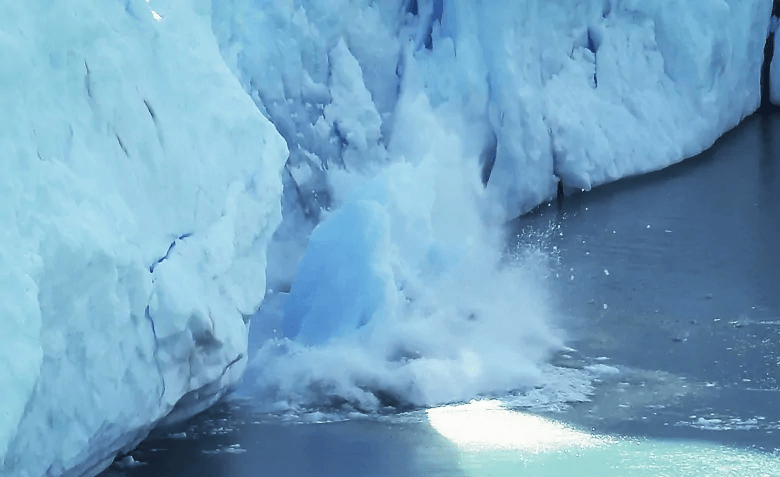

Take this to a global scale, where the ice covering the Arctic Ocean is currently reflecting sunlight back into space, keeping the planet cool. That ice is expected to disappear in summer within the next few decades, which will trigger a cascade of other warming effects.

Sunlight will be absorbed by the exposed dark seawater. The warmer ocean heats the Arctic, which causes permafrost around the North to melt, exposing ancient plant and animal remains, which rot and release methane, another greenhouse gas, that accelerates warming even further.

These dramatic and relatively sudden changes at the top of the world can influence ocean circulation patterns, which can shift weather systems. Eventually, events at the North Pole are affecting monsoons in India, half a planet away.

Before the fall

But as long as some of that ice remains, the system looks stable. And it is that stability under pressure that provides fuel for those who say climate change is not real, and more importantly, allows political leaders to delay making any real changes.

So, do we wait until the tipping point arrives, then try to put the wine back into the shattered glass, or do we back off now, before the fall?

A recent survey out of Université de Montreal showed that many Canadians are not concerned about the harm that could come from climate change. Perhaps that’s because the idea of shorter winters and longer summers doesn’t sound so bad. We are being lulled into complacency and inaction because, for the most part, it seems like not much is changing.

But we’re getting close. Some parts of the Canadian North have already passed the two degree temperature rise. To put that increase into perspective, the average global temperature has only gone up about five degrees since the last Ice Age, 10,000 years ago. So, a two-degree change in a hundred years is a lot.

Predictions of what will happen when the climate passes a tipping point can be pretty dire.

Exactly when the change happens, and how quickly the transition takes place, is difficult to predict, because this rate of change hasn’t been seen before. Warming and cooling trends in the Earth’s history have taken centuries or even millennia to happen. This one is happening in decades.

Whatever happens, the climate will settle into a new stability, which will be different from what we have today. How this will affect our agricultural areas, water supplies and tourist industry is anyone’s guess.

But the point is that if the climate changes into something we don’t like, there’s no going back.

About The Author

Bob McDonald is the host of CBC Radio’s award-winning weekly science program, Quirks & Quarks. He is also a science commentator for CBC News Network and CBC-TV’s The National. He has received 12 honorary degrees and is an Officer of the Order of Canada.

Bob McDonald’s Blog

Bob McDonald’s archived CBC columns, 2006 to June 2014

Credit to CBC & Bob McDonald