If you know where to look, the markets are telling you that they understand we’re moving into a new phase of US-dollar decay.

With the most recent dovish statement by Jerome Powell, the wheels have been set in motion for a fresh cycle of rate cuts. Going so far as to say he would do what it takes to “sustain the expansion”, I believe the Fed chair is preparing the market for a series of cuts that will send the Fed rate to 0%. This is the best possible news for America’s worst companies.

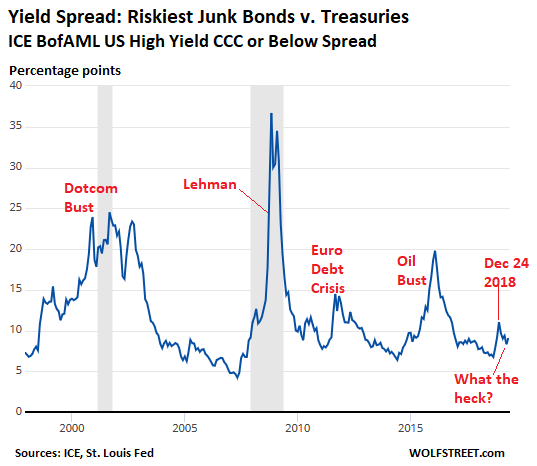

Junk bonds, the riskiest of all corporate bonds, should offer a significant percentage return to US Treasuries. As the chart below indicates, this is especially so when a recession comes into play.

It makes all the sense in the world when you learn that for the last 32 years, sub-investment-grade bonds, the junk rated CCC and lower, has defaulted at a spectacular 26.85% rate.

So we see that the spread between junk bonds and T-bills has soared during times of market crisis, maxing out at around 37% during the Lehman Brothers collapse.

So how is it that with 60% of National Association of Business Economics economists predicting US recession by 2020 — a result that would be ordinarily be fatal to many if not most of the riskiest junk-bond-issuing companies — junk bonds on the whole are returning a mere 8% percent premium above the perceived global safe haven of US Treasuries?

Because while a free-market recession would indeed be fatal to heavily indebted, money-losing companies, a free market is not what we have. Even before he came out and told everyone it would happen, the bond market predicted that Jerome Powell would meet the wet blanket of recession with a roaring forest fire of zero-interest rates and more QE.

With its decision in December 2018 to stop raising rates and signal a softer approach, the Fed basically said, “We know you’re a debt-ridden, operationally hopeless, industry dinosaur of a company. But here’s an unlimited source of almost-no-interest debt. We dare you to find a way to go out business.”

According to the Bank of International Settlements, fully 16% of American companies can now be classified as such so-called “zombie companies.” This is eight times higher than in the early 1990s and is a both a direct consequence of ZIRP (zero-percent interest rate policy) and the primary reason the Fed has no choice other than to return to ZIRP (and QE), probably for good, until the dollar is finally printed into oblivion.

Among these companies? We’re talking about former vanguard of American industry that globalization has rendered increasingly uncompetitive, household names like General Electric and US Steel. It’s entirely unclear how these companies turn things around in a world that leaves them further behind by the day.

But at the other end of the spectrum, how long could consumer darling Netflix survive if the cheap debt spigot were abruptly shut off? Nobody doubts the ongoing demand for their service, but that demand has been built on the back of $12B in primarily-content-acquisition-related debt. It loses money hand over fist, burns cash at a staggering rate; since 2011, the company has lost $13B.

So here’s the part the Fed really can’t say: 16% of American companies failing or faltering at the same time would be economically catastrophic. Which is to say the most indebted, most unprofitable American companies, put together, may have become ‘too big to fail’.

Which is why I believe interest rates are headed back to 0%.

Given that, what’s the real near-to-medium-term difference between the risk of default by companies that will never again (or, in some cases, won’t ever) be operationally self-sustaining (but who have already proven they can survive as long as they have access to super-cheap debt) and US Treasuries?

As the market is indicating, incredibly and realistically, not much.